Sir James Clendon Tau Henare

James Clendon Tau Henare was regarded at the time of his death in 1989 as the foremost kaumatua in Tai Tokerau.

He was the son of Taurekareka (Tau) Henare of Ngā Puhi and Ngāti Whātua descent and Member Parliament for Northern Maori from 1914 to 1938, and Hera Paerata of Te Rarawa, Ngāti Kahu and Te Aupouri descent.

He was born at Motatau, Bay of Islands, in 1911 and attended various schools in Tai Tokerau, Auckland and Wellington. He studied agriculture at Massey Agricultural College in Palmerston North but was unable to complete his studies because of illness. In 1933 he married Rose Cherrington, a distant cousin, to whom he had been betrothed at birth. They had six children of their own and five adopted children.

Sir James Henare’s father Taurekareka Henare

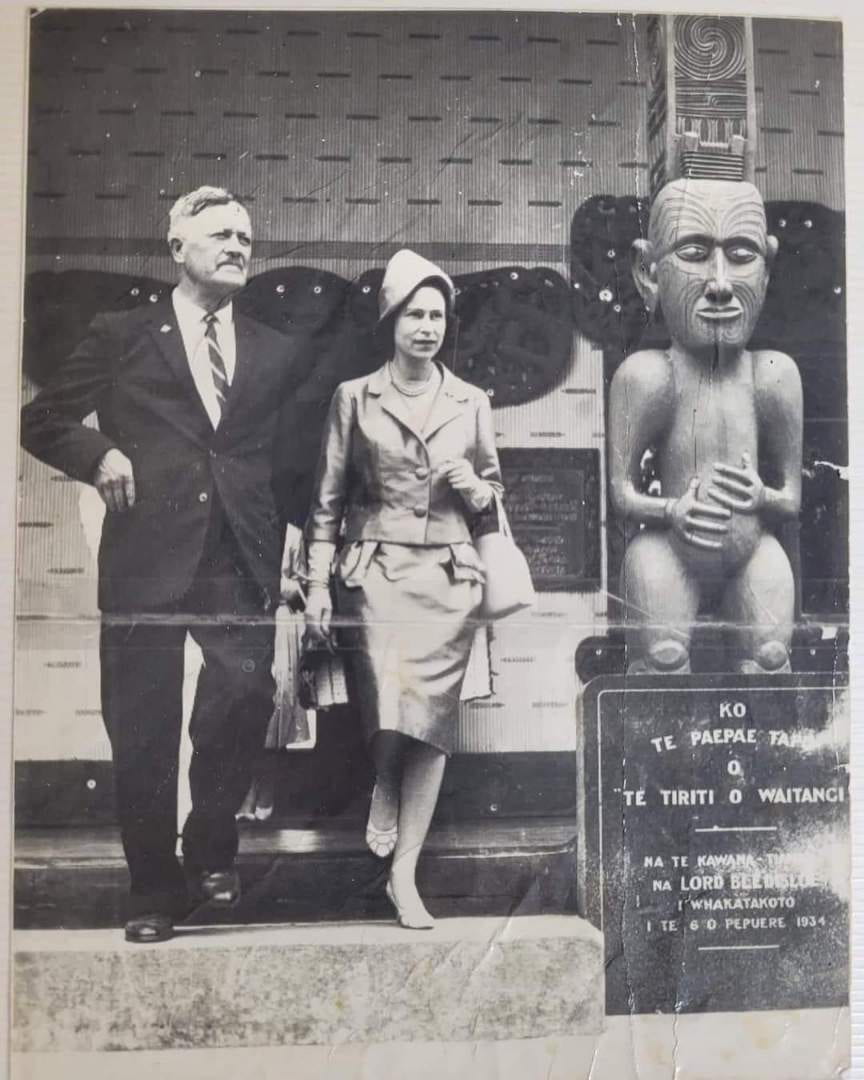

Sir James Henare and Queen Elizabeth II

Source: The Henare Whānau Archive

Leading role in 28th Māori Battalion

At the outbreak of the Second World War Sir James left his dairy farm at Motatau to join the army as a private. He rose to become Commanding Officer of the 28th Māori Battalion as Lieutenant Colonel, succeeding Arapeta Awatere in that role. He took part in all major actions in North Africa and Italy, was three times wounded and was awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order) in 1945. His valiance is described in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography:

Wounded at El Alamein in October 1942, Henare was mentioned in dispatches and in 1946 was made a DSO. The citation noted his fearlessness and courage, singling out his company command at Cassino in February 1944 and inspirational leadership in action in 1945.

Lieutenant Colonel James Henare, about 1945

Source: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography/Alexander Turnbull Library

Sir James Henare leading his battalion

Source: Henare Whānau Archive

Sir James Henare

Source: Henare Whānau Archive

Kōhanga reo movement

Sir James also took a leading part in establishing the kōhanga reo movement. He was its co-patron with Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu until his death in 1989. Sir James was made a Knight of the British Empire in 1978, having earlier received the honour of Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Ko te reo te mauri o te mana Māori.

Ko te kupu te mauri o te reo Māori .

E rua ēnei wehenga kōrero e hāngai tonu ana ki runga i te reo Māori.

Ko te reo, nō te Atua mai.

The language is the life force of the mana Māori.

The word is the life force of the language.

These two ideas are absolutely crucial to the Māori language.

A language which is a gift to us from God.

Honouring Sir James’ Work

In 1986, the University of Auckland conferred an Honorary Doctorate of Laws on Sir James, in recognition of his work for Māori culture, the guidance he had given to the University in its continuing development of Māori Studies, and not least for the part he had played in assisting the establishment of the University marae, Waipapa.

To honour Sir James’ achievements and to further his aspirations for Tai Tokerau, the University accepted the recommendation made by Ngāti Whātua that the newly established Māori research centre should bear his name when it was opened in 1993.

Though a noted orator in English and in Māori, Sir James will be remembered as much for his unstinting service to others, for his deeds rather than his eloquence, and for his honour among all his countrymen, rather than his honours.

Above all, he was a man of integrity, and one who managed to move freely and graciously between Te Ao Māori and the worlds outside. He was a practical and successful farmer and a dedicated family man (supported always by his beloved wife, Lady Henare), a politician who was always also a statesman, a diplomat, a scholar and a man of the people.

Sir James was truly a ‘man for all seasons’, something that is underlined by two things. His family insisted the research centre named after him should bear his name devoid of any titles – “he was always ‘Jim’ to everyone who knew him”.

After his death, a vast throng of people from every walk of life journeyed to Otiria and Motatau to participate in the tangi and funeral. He was laid to rest in the wāhi tapu overlooking the school and marae. It was named Takapuna in memory of the place where his mother, Hera, died from influenza, caught while helping to look after the victims of the 1918 flu epidemic.

As the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography says:

Henare was emphatic that New Zealanders had to become truly bicultural before they could become multicultural, and he was critical of certain Pakeha attitudes and condescension. He saw Maori values of personal relationships, relaxed lifestyles, hospitality and creative skills as beneficial to the country as a whole. Although not regarded as an activist, Henare had strong views, which he invariably explained in a reasoned manner. He was not greatly concerned about the heat generated by debates on the treaty as he believed there were reserves of goodwill on both sides. His personal mana was marked by a statesmanlike demeanour, a positive adherence to Māori values and an unfailing courtesy.

Education is the great liberator

Sir James believed passionately in education as a liberating force, and fought for an education system that would recognise local and Māori needs within the overarching framework of the Treaty of Waitangi. Like many of his ancestors, he regarded the Treaty as a covenant which Tai Tokerau in general and Ngāti Hine in particular had a sacred duty to safeguard and to keep in the forefront of public consciousness.

He was acutely aware of the danger of simply throwing money at problems which could only be solved by personal effort and changes of attitude. He was, for example, concerned that over-dependence on state funding could subvert the kōhanga reo movement of which he was a staunch champion.

Like Thomas A. Beckett in TS Eliot’s play, he saw the need to take care lest we end up doing the right thing for the wrong reason, and lose sight of the goal for which we should really be striving. At the same time, he was also mindful that lack of legitimate public good finance could be acutely damaging to community welfare.

He and his cousin-in-law, the late Hori Waititi, fought a long battle to retain the district high school in Motatau, realising its importance and potential as an educational centre for all of Ngāti Hine. Although the system eventually defeated them, the rightness of their cause and steadfast example has inspired others since to engage in similar struggles, some of which have for the time being at least, succeeded.

It is rumoured with some authority that towards the end of his life Sir James was being seriously considered as a future Governor-General of New Zealand. He would undoubtedly have filled this role superbly.

Biographic details provided courtesy of Professors N Tarling, H Kawharu and R Benton, and the Henare family.

The Governor-General Sir David Beattie and Taitokerau Elder Sir James Henare, seated outside the Meeting House at Waitangi. Photographed by an Evening Post staff photographer on the 7th of February 1984.

Source: National Library

Sir James Henare meeting with young Māori at the alternative marae, Whare e Manaaki, Kensington Street, Wellington. From left: Waki (Paula McKinnon’s brother), Ms Lorraine Skipper, Paula McKinnon (Ms Skipper’s daughter), Sir Henare, Roiho Keretene (Sir James’ wife). Photographed circa 26 March 1983 by Evening Post staff photographer Ross Gibliin.

Source: National Library

Sir James through the eyes of his Mokopuna

Tā James Henare’s twin grandsons reveal the intimacy they shared with the man they called Karani Papa.

Source: Waka Huia (YouTube)